|

December

20, 2005

The First Worlds War

|

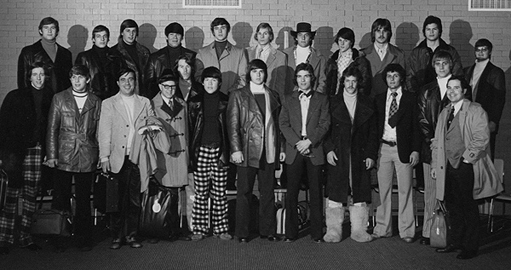

| Front Row L to R: David

Geving, Don Madson, Mike Radakovich, Assistant Mgr, George

Nagobods, Dave Heitz, Earl Sargent, John Shewchuk, Mark

Lambert, Mike Dibble, Dan Bonk, Paul Holmgren, Murray

Williamson, Coach/General Manager Back Row L to R: Tom

Ulseth, Jim Warner, Pete Roberts, Gary Sargent, Steve

Short, Tom Funke, Steve Roberts, Greg Woods, Craig Hammer,

Mike Wong, Al Mathieu, Trainer. (Photo

courtesy of www.murraywilliamson.org) |

The

first World Junior Championship was held in the Soviet Union

in 1974. Team USA endured just about every hardship imaginable

– and that was just on the trip there.

By

Jayson Hron

Donning

the red, white and blue at the World Junior Championship has

always been an honor – but it’s become much less

of an adventure.

Prompt

transportation, safe food and drink, comfortable hotels –

they’ve become the standard for today’s WJC competitor,

but it wasn’t always so. Especially not in 1974, before

the event carried an official title and sanction from the

International Ice Hockey Federation.

In

1974, the World Junior Championship was nothing more than

a six-team scuffle with major aspirations. It was a first-of-its-kind

meeting of hockey superpowers, conducted behind the Soviet

Union’s Iron Curtain.

Mike

Dibble, whose 50 career goaltending victories rank seventh

all-time at the University of Wisconsin, was among the American

contingent at the event. He backstopped Team USA to its only

victory, a 3-2 triumph over Czechoslovakia in the final contest

that assured a better-than-last-place showing for the upstart

travelers.

What

happened on the ice, however, was just a small slice of the

excitement for Team USA.

“We

flew to Montreal first and played in the Montreal Forum, which

was fantastic,” said Dibble. “Then we flew out

of Montreal to Bratislava.”

Team

USA’s next stop was Prague, where an exhibition game

against the Czech National Team loomed.

“That’s

when they lost our equipment – on purpose,” said

Dibble. “Things were very different back then.”

Without

their gear, Dibble and his teammates were stranded at a draconian

Prague hotel with nothing to do on New Year’s Eve. The

silver lining was edible food and palatable drink. Upon their

eventual arrival in Moscow, there was no silver lining.

“We

got there about noon,” said Dibble. “We saw Stalin’s

grave, then we sat at the train station where we were delayed

and delayed. We were supposed to take this train called the

‘Bratislava Bullet’ to Leningrad but the train

left at midnight and arrived at like 7 a.m. so you couldn’t

see their country side. At least that’s what we figured.

The

First Shift |

| Members of the U.S. Team

that took part in the inaugural World Junior Championship

in 1974. |

| Dan

Bonk |

Minnesota |

| Mike

Dibble |

Wisconsin |

| Tom

Funke |

Fargo-Moorhead

(MJHL) |

| Dave

Geving |

North

Dakota |

| Craig

Hammer |

Fargo-Moorhead

(MJHL) |

| Dave

Heitz |

Lansing

(IHL) |

| Paul

Holmgren |

Minnesota |

| Mark

Lambert |

Minnesota |

| Don

Madson |

Fargo-Moorhead

(MJHL) |

| Peter

Roberts |

Michigan

Tech |

| Steve

Roberts |

Providence |

| Earl

Sargent |

Fargo-Moorhead

(MJHL) |

| Gary

Sargent |

Springfield

(AHL) |

| John

Shewchuk |

Lansing

(IHL) |

| Steve

Short |

Philadelphia

(NAHL) |

| Tom

Ulseth |

Wisconsin |

| Jim

Warner |

Colorado

College |

| Mike

Wong |

Montreal

(QMJHL) |

| Greg

Woods |

Fargo-Moorhead

(MJHL) |

“The

problem was you couldn’t drink the water there. And

we were getting very, very thirsty. We hadn’t brought

anything of our own to drink. Well, the Canadians brought

a whole bunch of pop and when we saw them start loading their

pop onto the train, we went for that pop like kids go after

candy. I got three cans, so I was happy. Then the Canadians

saw us stealing their pop and there was a big fight, but that’s

how thirsty we were. Everyone was dying of thirst. It was

like an all-out riot.”

Eventually

the Americans arrived in Leningrad, bleary-eyed and sugar-filled

from several contraband pops. They hadn’t eaten in hours.

Breakfast was a top priority. Unfortunately, IHOP had yet

to arrive in Leningrad.

“The

food was absolutely inedible,” said Dibble.

Murray

Williamson, the veteran coach of many such international hockey

escapades – including the 1972 U.S. Olympic team that won the silver medal in Sapporo, Japan – was also

unimpressed with the fare and set out to remedy the situation.

“Murray

stood up to our Russian interpreter guy and said, ‘You

get us something to eat, that we can eat and get our strength,

or we’re out of here,’” said Dibble. “And

then they got in a big fight. But Murray did a great job standing

up for us and we finally got some food that we could eat.”

The

Americans’ next encounter came with a population that

knew real hunger all too well.

“When

we got off the bus, we were immediately surrounded by hundreds

of kids,” Dibble said. “They wanted anything you

could give them. Our bus driver told us we couldn’t

give them anything more because we were inciting a riot.”

The

players also couldn’t help but notice lines of people

waiting outside grocery stores. It was a society filled with

cravings, some primal and some just for fun.

“Walking

the streets was cool,” said Dibble. “And so was

meeting a Russian soldier under this bridge at midnight to

trade a pair of jeans for two Russian hats that I still have.”

On

the ice, Team USA opened the tournament against Canada, represented

by the OHL’s Peterborough Petes, who avenged the raid

on their pop with a 5-4 victory. The Canadians ended up finishing

third behind the Soviet Union and Finland.

Team

USA’s next opponent was Sweden, who trounced an uninspired

red, white and blue squad by an 11-1 margin. Finland then

stymied the Americans 5-1, leading to the eagerly-anticipated

meeting between Team USA and Khrushchev’s Comrades.

The Soviets won 9-1, leaving the Americans just one game to

regain their swagger.

“We

hadn’t won a game, and Czechoslovakia was a very good

hockey team,” said Dibble. “All I can remember

is that I had a lot of saves and the Russian crowd was chanting

‘DEE-bull, DEE-bull’ because they didn’t

like the Czechoslovakians. We won 3-2 and it was a great victory.

USA Hockey was at the bottom end at the time. It was really

instrumental that we didn’t come home shut out.”

Despite

their struggles, the 1974 squad helped set the foundation

for America’s hockey future. Thirty-two years later,

Team USA enters the WJC as the gold medal favorites with Boston

College’s Cory Schneider expected to serve between the

pipes. Like Dibble years before, he’s hoping for the

opportunity to sing the national anthem with a medal around

his neck.

“There’s

a lot of honor and respect that goes into putting on that

jersey,” said Schneider. “It’s a special

opportunity. USA Hockey has come a long way over the years,

with the National Team Development Program and the USHL. There

are a lot of good development programs throughout the country

that have helped Team USA become a force on the international

scene.”

Like

that of the travel-weary 1974 squad, it’s been a long

and memorable journey.

|